The Rabbi’s Role in Jewish Funerals

A Conversation with Rabbi Brian Schuldenfrei

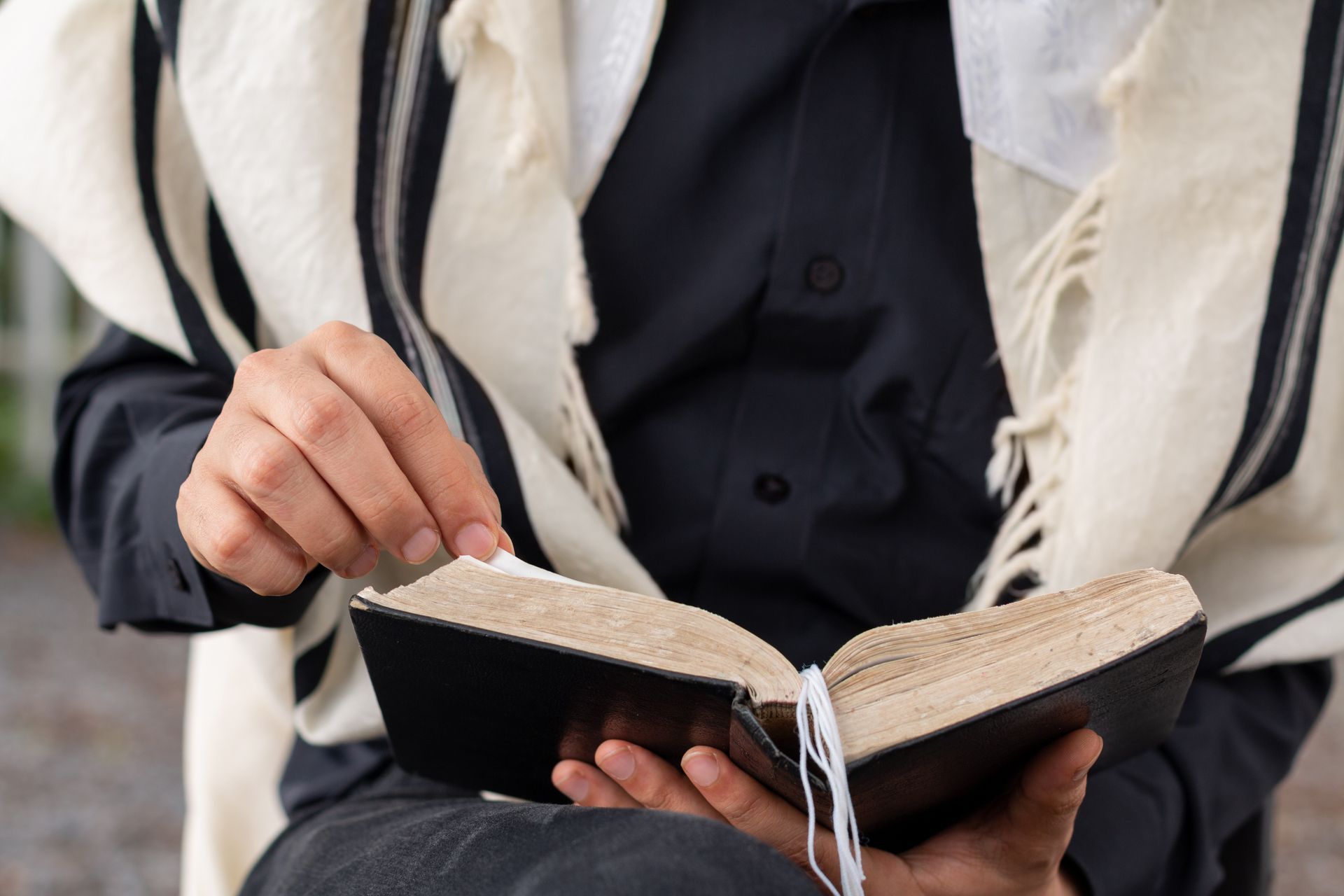

One of the most sacred and meaningful responsibilities a Rabbi can undertake is officiating a funeral—a moment of profound transition, reflection, and honor. It is a role that requires compassion, presence, and a deep understanding of tradition and community. To explore this sacred duty in greater depth, we sat with Brian Schuldenfrei, the senior Rabbi at Adat Ari El, a Progressive Conservative Congregation in Valley Village, to discuss his experience guiding families through the Jewish funeral and mourning process. In this candid and heartfelt interview, Rabbi Schuldenfrei shares the emotional, spiritual, and human aspects of his role, and the enduring power of Jewish ritual to bring comfort, connection, and dignity in the face of loss.

Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary (HMPM): Can you walk us through the key elements of a Jewish funeral service and your role in leading them?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: Often, when people learn that I’m a Rabbi and I officiate funerals, they ask, “Is that a difficult part of your job?” It can be, but it’s also one of the most rewarding. It’s a sacred honor to be entrusted with facilitating the ceremony that marks the closing of a person’s life. It is literally awesome, and it should feel weighty.

Funerals also vary widely. A funeral is largely about storytelling – telling the story of a person’s life. Sometimes, I tell the entire story; other times, I share it with family members, or I simply facilitate while others tell it. The goal is to help people celebrate that story while recognizing the loss and understanding that the story has concluded. It’s complex—so no two funerals are ever the same.

You also meet incredible people. I’m still in the process of burying members of the Greatest Generation; people who served in or lived through World War II. That generation tends to think first about their community, unlike younger generations who are often more self-oriented. For them, their lives are Torah.

When I go home, I reflect on what I want to remember. When you’re officiating for the Greatest Generation, you’re often honoring people who made profound sacrifices for others.

We’re also now burying the Baby Boomers, and that brings its own reflection—they were the ones who protested for social activism and challenged the American status quo.

Every time, I’m asking “What is the story of this person’s life, and how are we going to honor that story?”

HMPM: How do you approach writing and delivering a eulogy (hesped) that honors the deceased while also comforting the mourners?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: The best way to write a eulogy is to listen—truly listen. Whether or not I had a personal relationship with the deceased, I listen to the family’s stories. Who are they? What was this person about?

It’s not unusual for someone to call me and say, “I’m ill, and I know you’ll officiate my funeral. I’d like to talk to you about that.” And if it’s a complete stranger, listening becomes even more essential. When I visit a family, I spend hours just listening. The goal is to tell the story they want to tell. There’s no single objective truth; each person will have their own takeaways. What matters most to me is honoring how the family wants this life to be eulogized, memorialized, and consecrated.

HMPM: In what ways do you provide spiritual guidance to grieving families before, during, and after the funeral?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: I try to provide presence; to simply be there for the family. Traditionally, people host a reception during Shiva or after the burial. Often, the mourners worry about logistics. Did the food arrive? In our tradition, it’s our responsibility as the community to handle that. Spiritual counseling, to me, means showing up – being there in person. Sometimes that means sitting quietly in someone’s home.

We also check in on families afterward. Our synagogue has hosted bereavement groups and we try to acknowledge that a family’s life has changed irreversibly.

For some, I’m just a religious functionary, fulfilling the deceased’s wishes. I may never see that family again. For others, members of our community, we follow up, offer ongoing support, and invite them into grief groups.

HMPM: How do you help families unfamiliar with Jewish funeral customs understand and participate in the traditions?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: I meet people where they are, with warmth and friendliness. I keep explanations simple. People are often overwhelmed, so I don’t want to overload them with information. I try to connect and be present with them.

The last thing I want is for them to feel judged. Sometimes people tell me what they think I want to hear: “Rabbi, we only went to synagogue twice a year, but it was really important to my husband – he never ate pork, etc.” But I just want to know how they loved this person and how this person loved them. It’s not my job to evaluate their Jewish observance. I want to hear how Grandpa told jokes, or that he had a mouth like a sailor. Let Grandpa be who he was. Don’t turn him into who you think I want him to be. I can connect his story to Judaism, whatever it is.

HMPM: What is the significance of the Kaddish in the mourning process, and how do you guide families in reciting it?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: It can be as simple as me standing with a family by the grave and reciting it slowly with them, using a transliteration. Sometimes, people begin to attend minyan during their mourning period and say it regularly. Often, regular minyan-goers are themselves mourners and they’re incredibly welcoming.

Kaddish is a testimony on behalf of the departed soul. It doesn’t even mention death – it’s an affirmation of life and divine greatness. Saying Kaddish means showing up and saying: this person’s life mattered.

HMPM: Can you describe your process for meeting with the family before the funeral? What information do you gather to personalize the service?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: I ask open-ended questions and spend time listening. I want to hear about the person’s character, their relationships, and how they were loved. I gather anecdotes, learn about their values, personality, quirks, and legacy. It’s about understanding how they made people feel – and how they should be remembered.

HMPM: What are some of the most common questions or concerns families have about Jewish burial rituals, and how do you address them?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: The most common question is, “How am I going to get through this?” And the answer is, “You don’t have to do it alone.”

Grief is overwhelming. Most people never imagined they’d be in this situation, and they don’t know how to navigate it. My job is to be present and take as much off their plate as possible so they can simply be. They’ll cry, they’ll laugh, they’ll tune in and out – and that’s okay.

In cases of long illness, the family may be physically and emotionally spent. Sometimes it just feels like one more thing to get through.

I think Judaism really understands mourning. We double down on grief and community. We don’t expect you to be okay – and we don’t leave you alone. We surround and support you.

Many people who experience Jewish mourning practices for the first time walk away with a deep appreciation for them. Even clergy from other traditions have said, “The way you do mourning is incredible.” And they’re right – it really is.

HMPM: Jewish funerals emphasize simplicity and tradition. How do you help families balance tradition with personal preferences?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: I always remind myself: it’s not about me.

I do have my boundaries and preferences. If I don’t feel I can officiate a funeral, I’ll help the family find a Rabbi who can support them.

Sometimes, I’m okay officiating even if the ceremony includes aspects I wouldn’t personally choose. I remind myself to honor their grief and their connection with the deceased. My job is not to impose my preferences but to support them in honoring a life.

But more importantly, just act like a human being. If a widow has just lost her husband, open the door for her. Get her a bottle of water. Help walk her dog. My job is to be there on one of the worst days of someone’s life.

They’d rather have their loved one back than this ceremony. So I always remind myself to ask “How can I help?”

Be kind. Be present. You won’t remove the darkness, but you can help make it a little more bearable.

What’s remarkable is that in these moments of grief, you often see the best of people and the best of community. When people have invested in their communities, those communities rise up to care for them. It’s incredibly affirming.

HMPM: What do you find most meaningful about your role in guiding families through the funeral and mourning process?

Rabbi Schuldenfrei: It’s emotional for us too. To have empathy, you have to feel it. If you knew the person, you’re going to miss them. And if you didn’t know them, you might wish you had.

Most Rabbis enter this field because they want to be of service. We’re present. We feel. We connect. And having that emotional range is so important in doing this sacred work well.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

We are immensely grateful to Rabbi Schuldenfrei for taking time to explain the emotional and practical aspects of the Rabbi’s sacred role in Jewish funeral tradition. If you have recently lost a loved one and need a Rabbi for an upcoming funeral, Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary is ready to assist your family in finding someone who matches your family’s values and traditions.

Please don’t hesitate to

reach out at 800-576-1994 for assistance from our compassionate staff.